When the first world war was declared on 5 August 1914 the British Army consisted of about 400,000 men made up from the regular full time army and territorial soldiers who were part time. All of them were volunteers and embarked to France as the British Expeditionary Force to answer France’s call under the terms of the Entente Cordiale. What followed was a series of battles and never ending skirmishes as each side tried to out manoeuvre the other and which developed into mutual hopscotch which ended on the Belgian coast. By the end of 1914 the BEF had lost 96,000 men but the allies had managed to stop the German advance. Field-Marshal Lord Kitchener, a national hero of the Sudan and South African campaigns, and Britain’s Secretary of State for War was one of the few people who believed that the campaign would be long and costly in terms of men and material. Two days after war was declared he made an appeal for recruits and the nation answered the call. By 12 September 1914 nearly 500,000 men had volunteered for Kitchener’s Volunteer Army.

Driven by patriotic fervour and an excellent advertising campaign they came in their droves, but the cornerstone of the drive was the simple yet brilliant but ultimately disastrous concept of the Pals Battalions. The concept was to allowing committees of councils, industry, other dignitaries or anyone who could master enough support, especially in northern England, to organise locally-raised battalions.

The simple promise was that men from the same community or workplace were encouraged to join on the understanding that they would train and, eventually, fight together. Disastrous because a lot of them died together as well.

Of 1,000 British battalions raised during the war 145 were Pals Battalions. They were based on whatever link of camaraderie could be made. Some were locality based like the Leeds or Accrington pals, some were based on an affiliation like former schoolboys of Wintringham Secondary School in Grimsby who enlisted as the Grimsby Chums or the entire first and reserve team players, several boardroom and staff members, and a large contingent of supporters of Scottish professional football club Heart of Midlothian and some were based on a trade/social-background rather than a location such as the public school battalions or the stockbrokers.

The reasoning behind this recruitment strategy is easy to explain, This was a volunteer army and as such needed volunteers. It is doubtful that any other method would have as successful in raising the number of volunteers that was going to be required. In the first weeks of the war, Lord Derby took up the idea suggested by Sir Henry Rawlinson, of encouraging whole towns and villages to sign up together. They were promised that they should also serve together with their friends and relatives which was invariably honoured.

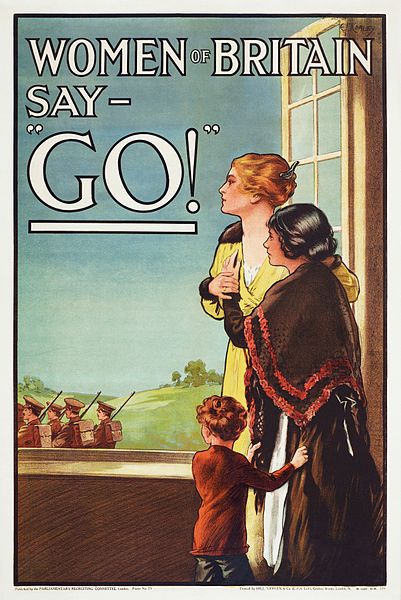

I can also imagine that once the idea took hold a fair amount of peer pressure came into play. Such was the patriotic fervour at the time men would march out of workplaces, pubs and clubs to get down and recruit. Imagine being the one or two guys left behind as all their friends watched on scornfully. The propaganda at the time was such that recruiting went into overdrive with posters and campaigns inciting volunteers and deriding the ones slow to sign up. The common theme in the recruitment drive was one of all being in the fight together, of doing your part and being a slacker or a coward if you didn’t if you didn’t and a sense of shame if you didn’t join up.

The volunteers started their training locally and could often train while still living at home, meeting other pals down the pub. There would have been an enormous sense of shared experience. Men, women and children from local communities all pulling together for the common cause. Posters showed the women encouraging their men folk to go and fight.

It was all very jingoistic and patriotic. What few knew was Kitchener’s belief that the war would be won by the side with the last million men standing. There are numerous opinions and discussions on the use of 18th century tactics in light of the new paradigm of industrial scale warfare, but how did the battalions fare?

On 1st July 1916 the sun shine brightly across the country side of northern France north of the River Somme and is seen as the first day of now well known story of the Battle of Albert in the months long Somme campaign.

The battle had actually started seven days earlier when British artillery pieces commenced firing 1.73 million shells at the German defenders expecting to suppress any defence to the coming infantry attack. The German defenders, many of whom had been in place since 1914, had had ample time to reinforce their positions and even that immense number of guns and shells were later found to have been insufficient to suppress the defences and destroy the enemy’s ability to defend. Because they had ample time to prepare the German lines were extremely deep and extremely well made, protecting them from artillery fire. A lot of the shells fired were duds and in general did not have enough high explosives to penetrate the bunkers. At 7;30 am when the whistles sounded and thirteen British and six French divisions, 100,000 men, went over the top into what turned into the worst day in British military history with over 57,000 casualties including almost 20,000 dead.

The contingents of Pals Battalions in their regiments were in the thick of it and the casualty lists for them makes sobering reading especially given the bravado, good cheer and optimism which had accompanied their formation.

Over 700 Accrington Pals advanced from their trenches before the fortified village of Serre, north of Thiepval. In less than 20 minutes 235 of them were dead and 350 wounded. Contemporary reports says that not one man wavered or turned back.

With them were 750 Leeds Pals of whom 248 either were killed or died from their injuries. By nightfall that day only 72 members were left uninjured.

Of the members of the Hearts of Midlothian team, who were the best team in Scotland when the conflict broke out, sixteen members of the first team went off to battle, seven died in action, two more succumbed to the effects of gassing and a tenth was crippled in the fighting and never played again. The battalion suffered 229 casualties on the first day of the battle of the Somme.

And the Grimsby Chums? Of the 600 man battalion who fought on 1 July 1914 they suffered 502 causalities.

When the fighting on this front finished on 18 November 1916 British troops had sustained 420,000 casualties, including 125,000 deaths. The French suffered 200,000 casualties and the German Army 500,000.

The losses sustained by the Pals Battalions affected not only their effectiveness as fighting units but the communities that they had left back home. After the Somme the Pals battalions simply did not have enough men left to form on their own and many were disbanded and the remaining numbers folded into other units. By the end of the year, Britain would have to introduce conscription for the first time in order to continue raising troops. The idea of the Pals started in a spirit of community, patriotism and comradeship had been shattered in the mud of the Somme, and so had many of the communities they had left.

Families lost all their male members. Whole neighbourhoods lost most of their young men in a single day, as volunteer battalions took heavy losses at battles such as Ypres and the Somme. Many of the cotton towns of Lancashire, where I grew up, had the heart ripped from them. Each day, pages and pages of casualties in the local papers, street, towns even the whole area went from a common cause to a common loss. In Leeds it was that there was not a street in Leeds that didn’t have at least one house with curtains drawn in mourning.

The Pals Battalions were actually a good idea which recruited the men required in a sort period of time. Comradeship and a sense of belonging were already built in, men wanting to fight with and for their friends and relatives. Even families back home would have taken some comfort in them looking out for one another. It would be unfair to say that no-one foresaw the downside to this, the chance of wholesale loss. And it was that which is often remembered, in hindsight. No-one expected the first day of the Somme, the battle was not supposed to play out the way it did. It had been planned meticulously but there were too many unknowns and many bad assumptions made.

But the battle had broken the German Army’s morale and inflicted massive casualties that they struggled to replace with the same quality of soldier.

A German writer asserted “the tragedy of the Somme battle was that the best soldiers, the stoutest-hearted men were lost; their numbers were replaceable, their spiritual worth never could be.”

The weakened German Army retreated to shorter defensive lines in February 1917 and German Commander, Ludendorff, was also quoted as saying, “The German Army was fought to a standstill on the Somme and utterly worn out…not only did our morale suffer, there was fearful wastage in killed and wounded…we had not enough men.”

The Battle of the Somme cost 1.2 million casualties. A dreadful price to pay but believed to have been the beginning of the end of the World War One.